While it has presented a masterclass in mass delusion, this has come at the cost of the dignity of almost all the participants. In the noise, the truth is lost; worst of all, South Africa’s children are no nearer securing the good education they deserve.

The thesis driven by the department is that racism is the greatest obstacle standing in the way of providing access to good schooling for children in the province.

From the Koeitjies en Kalfies Kleuterskool in Centurion to St John’s College* in Houghton, and most recently the Hoërskool Overvaal, the department and its officials have been quick to sweep up racial nationalist hysteria in an effort to reinforce the thesis. Along the way, the politicians and officials present themselves as patriotic South Africans whose deep commitment to justice for poor children sees them going to heroic lengths to ensure that every child can be afforded a good education. It is an act that is ever less believable.

Consider some of the national data:

In Gauteng:

One of the arguments advanced for poor levels of achievement in education is that schools in richer areas refuse to open their doors to poor pupils. This is wrong, as most of these good urban schools are oversubscribed.

The real problem rests in the fact that many urban schools produce very poor results, and this cannot be addressed by sending all their pupils to the minority of schools that maintain high standards.

A second argument is that there is too little money within the State and that officials are therefore unable to provide access to better quality schools. But this argument also falls apart. South Africa’s per capita spending on education and its spending as a share of GDP is competitive with emerging markets that outperform it on education benchmarks year after year.

A peripheral argument is that Afrikaans is being used to deny black children access to proper schools. Notwithstanding the fact that a majority of Afrikaans speakers are black and that it is the second most-spoken home language after Zulu and Xhosa (English is behind Afrikaans), only 5% of schools are Afrikaans single-medium schools. It is nonsensical that this figure explains why the majority of children receive such a poor standard of education.

There are strong education policy reasons why one should be cautious about the arguments commonly advanced in explanation of poor education outcomes at school level, and these are often lost in the noise and emotion.

IRR research, some of which is soon to be published, shows that high levels of parental and community decision-making over school policy is important in achieving good results. There is also an important body of evidence that mother-tongue education may improve the learning potential of pupils.

It is overlooked that the demand to be taught in English may be the primary reason for poor levels of education achievement among non-mother tongue speakers. But South Africans cannot even examine the evidence when politicians and activists adopt the default position that mother-tongue education is code for racism.

There is also a lot of hypocrisy in the debate about school education, with many commentators and parents educating their own children in their mother tongue or sending them to excellent government schools with high levels of parental management involvement, or even private schools – but demanding that politicians deny other parents similar decision-making autonomy over how to raise their children. It is enlightening to ask any activist who makes such demands where they were educated or where they send their own children to be educated.

The more compelling reasons why only 3/100 children will get a good maths pass in matric, and why approximately half of children will drop out of school, relate to corruption, poor planning, and ineffective management of existing resources.

Denying a child the chance of a bright future will drive any parent to extreme levels of anger. Politicians who, with good reason, are afraid of the consequences, especially in a politically vulnerable province like Gauteng, would rather that parents did not come to focus on things like below 50% pass rates in maths. Hence the effort made to focus public anger on other issues such as racism and Afrikaans.

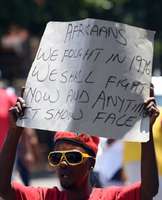

The political formula is easy: make some outrageous allegation based on a sliver of truth and appeal to the media’s bent for the pitiful drama put into motion when the most reptilian of politicians conspire through half-truths and populist incitement to turn two fundamentally decent but equally desperate racial or ethnic communities against each other and threaten violent disorder. Ferry in a crowd of protesters, make sure some wet-behind-the-ears click-bait focused junior journalist fresh out of media school is there with his or her cellphone to draw the voyeuristic public into the wretched scenes of the desperate parents fighting for the chance that their children might go to a good school. Then bring out the riot police, and you are assured of another week of not having to answer tough questions about the schools your department runs.

None of the participants come out looking good, least of all the journalists who milked the desperation behind the Overvaal clashes almost to the point of public entertainment. It would have been no less distasteful had they staged physical fights between parents in their newsrooms, sold tickets to the spectacle, and promised a bursary to the child of the winner.

As for the official political opposition, the best it could muster was to make some asinine remarks about inclusion and unity and the importance of not resorting to violence. If it thinks telling South Africans to unite and not throw rocks at each other is a policy position that can provide the leadership to resolve crises on tough issues such as those at Overvaal, then it has a hell of a surprise coming in the 2019 election.

There has of late been criticism of the vacuous nature of the communications and policy thinking of the official opposition. Its inability to muster any intelligent analysis or adopt any firm position on the Overvaal crisis was another disappointment.

Root out racism where it exists – of the importance of this there is no question. But parents, commentators and journalists should be careful not to be so easily swayed by populist politicians and media fervour that they come to overlook (or even remain unaware of) the more substantive reasons pointing to why many children are still denied a good education.

- Frans Cronje is a scenario planner and CEO of the IRR – a think tank that promotes political and economic freedom.

*The author attended St John’s College, but holds no position on any governance or other body of the school.

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026