South African Institute of Race Relations NPC

Submission to the Economics Tax Analysis Chief Directorate,

National Treasury,

regarding the Policy Paper on

Taxation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages of 2016

Johannesburg, 22nd August 2016

Introduction

The Economics Tax Analysis Chief Directorate of the National Treasury (the Treasury) has invited public comment on the Policy paper on the Taxation of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages published on 8th July 2016 (the policy paper).

Public comment is due not later than 22nd August 2016. However, this period is too short to meet the constitutional requirement for proper public consultation. It would also have been helpful if the policy paper had been accompanied by an initial socio-economic assessment of its likely economic and other ramifications, as envisaged in the government’s new Socio-Economic Impact Assessment System (SEIAS).

This submission is made by the South African Institute of Race Relations NPC (IRR), a non-profit organisation formed in 1929 to oppose racial discrimination and promote racial goodwill. Its current objects are to promote democracy, human rights, development, and reconciliation between the peoples of South Africa.

The tax proposed

The tax is to be levied on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), which are defined in the policy paper as ‘beverages that contain added caloric sweeteners such as sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), or fruit-juice concentrates, which include but are not limited to: (i) soft drinks, (ii) fruit drinks, (iii) sports and energy drinks, (iv) vitamin water drinks, (v) sweetened iced tea, and (vi) lemonade, among others’. Any beverage that contains only sugar that is ‘naturally built…into the structure of the ingredients’, ie intrinsic sugars, is to be excluded from the tax. Examples of such beverages include unsweetened milk and 100% fruit juice. [Policy paper, pp2-3]

The tax is to be levied on the basis of the sugar content of the relevant beverages and will (the policy paper says) be ‘in direct proportion to the level of added sugar in SSB’. [Policy paper, p3] The proposed tax rate is 2.29 cents per gram of sugar on beverages where the sugar content is reflected via a label. According to the policy paper, ‘this rate roughly equates to a 20 per cent tax incidence for the most popular soft drink, ie Coca Cola, averaging 35g per 330 ml’. [Policy paper, page 3]

A higher sugar content will be presumed for ‘SSBs that currently do not apply nutritional labelling’, at 50g per 330ml. This, the policy paper says, is intended to provide ‘an incentive for producers to move towards nutritional labelling until [a] mandatory labelling legislative framework is put in place’. [Policy paper, p3] However, as journalist Ivo Vegter comments, this is ‘a punitive’ assumption which presumes the sugar level in such beverages to be 43% more than the sugar contained in Coca Cola. [Ivo Vegter, ‘Tax on sugar-sweetened beverages is arbitrary and unnecessary’, August 2016, p1]

Differential impact of the proposed tax rate

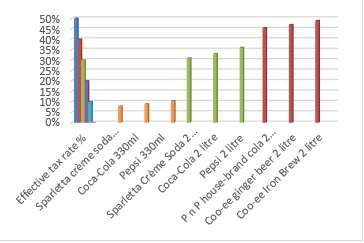

Most countries that have introduced a tax on SSBs have used a flat tax rate per litre. Only Mauritius has what South Africa proposes. The idea, based largely on (unconvincing) research by Professor Karen Hofman and others at the School of Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand (see below), is that the tax should increase the price of SSBs by some 20%. Since a litre of Coca Cola (Coke) contains 106g of sugar and retails for roughly R11.50, this has led to a proposed tax of 2.29c per gram of sugar. However, as City Press reports, this approach will result in significantly different price increases for products of varying sizes and sugar content. [City Press 24 July 2016]

As Dewald van Rensburg writes in City Press, where SSBs are sold in small units, such as 330ml cans, the impact of the tax on the price charged (assuming the tax is passed on in full) will be less: ‘A 330ml can of Coke goes for R9 at Pick ‘n Pay, but 2 litres cost R14.50. The proposed tax would add 9% [to the price of] a can of Coke, but 33% [to the price of] the 2-litre bottle.’ Price increases will thus be greatest for consumers who seek to buy in larger quantities in an attempt to reduce their expenses – and also for producers who sell in these larger quantities so as to target the low-cost end of the market. [City Press 24 July]

The proposed tax could hold particularly negative ramifications for SoftBev, which bottles not only PepsiCo products but also lower-cost local products such as Coo-ee and Jive.

Writes Mr van Rensburg: ‘Coo-ee is usually priced lower than Coca-Cola products and is sold only in large units. At the current price, the tax would [add] close on 50% to [the price of] some Coo-ee products’ (see Table 1 below). The tax could inhibit competition in the soft drinks industry by ‘squeezing out “B” brands’. [City Press 24 July 2016]

Table 1: SSB tax price increases on various sizes and brands of sugary drinks

This assessment presumes that the SSB tax will be fully (100%) passed through by retailers. Larger enterprises could, however, shoulder some of the increased price and pass through only a portion of the tax. However, smaller retailers with limited turnover – especially those operating in spaza shops and the like – will have less capacity to absorb any part of tax and could have little choice but to pass it on to consumers in full. This could reduce their sales volumes, causing them significant harm (see The likely economic costs, below).

According to a recent Business Day editorial, ‘estimates are that the tax could bring in R3.6bn to R4.5bn’ a year in additional revenue. This assessment under-estimates a tax yield more likely to amount to some R10.5bn (see The likely economic costs, below), but the amount in issue is still more small compared to a total tax take of about R1 trillion. [Business Day 12 July 2016] According to the Treasury, the primary rationale is not to increase the government’s tax take but rather to help counter the problem of obesity within South Africa. [Policy paper, pp4-30]

Reducing obesity the supposed rationale

Obesity is becoming a major problem not only in South Africa but also in many other countries around the world. As the policy paper points out, the prevalence of obesity is measured using a ‘body mass index’ (BMI), based on the formula: weight in kilograms, divided by height squared (kg/m2). A person with a BMI level of 30 or more is classified as obese, while an individual with a BMI level of 25 or more is regarded as overweight. [Policy paper, p4]

BMI readings vary greatly across countries. In South Africa, almost half the adult population has a BMI of 25 or more, while 23% of adults have a BMI of 30 or more and are thus obese. Obesity is significantly more pronounced among women (33%) than men (12%). (By contrast, some 68% of adults in the US are overweight, with a BMI of 25 or more, while 32% are obese, with a BMI of 30 or more.) [Jasson Urbach, IRR Policy Fellow, unpublished analysis, 2016, p2]

These figures are derived from the World Health Organisation (WHO), in its Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014). However, the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Obesity Collaboration gives different figures: and it is these which are cited by the policy paper, at 13% among adult men and 42% among adult women. [Policy paper, page 4, citing Global Burden of Disease 2013 Obesity Collaboration, Global, regional and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis, The Lancet, 30 August 2014]

Somewhat different figures are also provided by the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1), which was carried out by South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) and Medical Research Council (MRC) in 2013. This survey puts the prevalence of obesity among adult men in South Africa at 11%, and the equivalent figure among women at 39%. [Vegter, 2016, p1]

Both in South Africa and elsewhere in the world, women are generally more prone to obesity than men. Prevalence is also generally higher among those who have less education and a lower socio-economic status. [Urbach, 2016, p2; Vegter, 2016, p1]

A wide range of economic and other policies have been developed to tackle obesity. Non-economic policies include detailed nutritional information to help consumers make more informed choices, mass media campaigns to raise awareness of health risks, the regulation of food advertisements, and the promotion of exercise and active sports. Economic policies include taxes on foods and beverages regarded as unhealthy, as well as subsidies or tax exemptions for foods and beverages seen as positive for health. However, overweight and obesity rates continue to increase in many countries, both developed and developing. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), no OECD country has managed to reverse the trend since rates began growing steadily across most OECD countries in the 1970s and 1980s. [Urbach, 2016, pp2-3]

Part of the problem, as IRR Policy Fellow Jasson Urbach points out, is that ‘industrialised food processing and modern food science have made a vast range of low-cost, ultra-processed and ready-to-consume products available to consumers with intense palatability… Ingredients typically include a combination of highly refined sugars and starches, edible oils extracted from whole foods, processed animal products, sodium, and other additives. These ultra-processed products are harmless when consumed in small amounts with other healthy sources of calories. However, in large quantities, the products diminish the sensitivity of endogenous satiety mechanisms and so promote energy over-consumption.’ In addition, though alternatives are often available to consumers in the form of fresh and perishable goods, these are often not as palatable. They also require greater preparation, which further lowers their appeal for many. [Urbach, 2016, p4]

Though obesity is a complex condition with many causes, its particular drivers seem to include a large increase in the availability of cheap vegetable oils (for improved techniques have increased the oil content of seeds, along with our ability to extract edible oils). In addition, the intensive production of beef, pork, dairy products, eggs, and poultry has increased food intake from animal sources, especially in low- and middle-income countries. There has also been a widespread reduction in the intake of nutritionally important foods, including legumes, coarse grains, and fresh vegetables, while a growing proportion of foods and beverages now contain caloric sweeteners to enhance flavour. All these factors have contributed to a ‘nutrition transition’, from traditional to ‘westernised’ consumption patterns, which has added to the obesity problem. [Urbach, 2016, p5]

A growing and multifaceted obesity challenge

In 2014 the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI or McKinsey) published a discussion paper entitled Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis (the McKinsey study). [Richard Dobbs et al, ‘Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis’, McKinsey Global Institute, November 2014] The McKinsey study identified obesity as a ‘critical global issue’, as nearly 30% of the global population, amounting to more than 2.1 billion people, are now overweight or obese. Of this total, some 671 million are obese. [Dobbs, 2014, In brief; www.healthdata.org.news/news-release/nearly-one-third-world%E2%80%99s-population-obese-or-overweight-new-data-show]

According to the World Health Organisation, obesity contributes to some 5% of global deaths, accounting for some 2.8 million global deaths a year on a base of 59 million global deaths a year. [Dobbs, 2014, p1] As the policy paper notes, there are various other factors which account for higher proportions of global deaths – high blood pressure is responsible for 13 per cent of such deaths, while tobacco use accounts for 9 per cent and physical inactivity for 6 per cent [Policy paper, p4] – but obesity nevertheless remains a major concern.

Obesity also contributes to a number of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases (such as heart attacks and strokes), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases (such as asthma) and type 2 diabetes. [Policy paper, p4] These diseases add significantly to health care costs, while obesity reduces the productivity of employees and undermines the competitiveness of companies. [McKinsey study, p1]

The complex causes of obesity

As the McKinsey study stresses, the causes of obesity are complex and varied: ‘The root causes of rising obesity are highly complex, scanning evolutionary, biological, psychological, sociological, economic, and institutional factors’. A study by the United Kingdom (UK) government on the reasons for obesity has thus identified ‘more than 100 variables that directly or indirectly affect obesity outcomes’. [Dobbs, 2014, p12]

Adds the McKinsey study: ‘Because of centuries of food insecurity, human beings have evolved with a biological capacity to cope with food scarcity rather than abundance. The human body seeks out energy-dense foods and tries to conserve energy as fat. Hormones that regulate hunger and satiety encourage people to seek extra food when food is scarce, but do not seem to have the ability to prevent over-consumption or encourage extra calorie burning when food is abundant. Modern life makes fewer physical demands on many people, who lead less active lifestyles as technology replaces the need for physical labour. With many jobs now sedentary, exercise is a conscious and optional choice.’ [Dobbs, 2014, p12]

This has greatly affected the net energy balance, and added to the risks of people putting on weight if they eat more than they need and exercise too little. At the same time, the cost of food has come down sharply over the past 60 years. In the United States (US), for instance, as the McKinsey study records, ‘the share of average household income spent on food fell from 42 per cent in 1900 to 30 per cent in 1950 and then to 13.5 per cent in 2003’. [Dobbs, 2014, p13]

More complex factors also seem to be in issue, though these still require more research. For example, there is growing (but still insufficiently substantiated) evidence that different nutrients may have a differential impact on the hormones that regulate satiety and hunger. In addition, people with a greater diversity of bacterial species in their intestinal bacteria ecosystem seem to be less likely to gain weight than others, though this too needs more investigation. [Dobbs, 2014, p13]

Psychological and social factors also play a part in what people eat. Notes the McKinsey study: ‘Human beings also have a psychological relationship with food that goes beyond a need for basic sustenance. Many of us use food as a reward or to relieve stress, or have a compulsive relationship with certain types of food. There is also a correlation between obesity and high rates of some mental health conditions, including depression.’ [Dobbs, 2014, p4]

Social norms and cues also have significant influence, for people increase or reduce the amount of food they eat at a given meal depending on whether their companions eat a lot or a little. In addition, a person with a friend who has become obese is 57% more likely to become obese as well, in response to this ‘social normalisation of the condition’. [Dobbs, 2014, p13]

There is also evidence suggesting that obesity can be passed on from generation to generation through both physiological and behavioural mechanisms. A mother with high BMI is likely to have children who also become obese when they grow to adulthood. This is partly, as the McKinsey study notes, because ‘foetuses develop a compromised metabolism and a resistance to insulin’, but also because children are likely to develop the same eating habits as their parents. [Dobbs, 2014, p25]

In many countries, there also seems to be an inverse correlation between income levels and the prevalence of obesity in women (and hence often also in their children). A study conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that obesity prevalence is generally similar at all income levels for men in the US (about 30 per cent), whereas for women it was 42 per cent at low-income levels and 29 per cent at high-income levels. A similar pattern is evident in the UK, for the prevalence of obesity is almost double among women with unskilled occupations (35 per cent) than among professional women (18 per cent). [Dobbs, 2014, p24]

Tackling a condition with many complex causes

As the McKinsey study stresses, ‘obesity is the result of a multitude of factors, and therefore no single solution is likely to be effective in tackling it’. A range of interventions is needed to ‘encourage and empower individuals to make the required behavioural changes’. In addition, ‘these interventions need to be systematic, not only aiming for immediate impact on the net energy balance but also making sure that the change is sustained’ over time. [Dobbs, 2014, p31]

The McKinsey study thus identified 74 relevant interventions that were being discussed or piloted around the world. These 74 interventions fall roughly within 18 groups, and can be analysed within the context of four key needs: (i) to inform people, (ii) to enable them (by making the option to change easier), (iii) to motivate them, and (iv) to influence them by addressing social norms. [Dobbs, 2014, pp32-35]

The McKinsey study also found that ‘there had been little systematic attempt to analyse the relative potential cost-effectiveness and impact’ of these various interventions. It managed to gather information on 44 of these 74 interventions, covering 16 of the 18 possible areas. In doing so, it conducted ‘an extensive review of more than 500 research studies from around the world’. It also ‘pressure-tested’ these studies on factors such as the quality of the research design and the comprehensiveness and relevance of the evidence cited. However, since ‘the science of addressing obesity is relatively young’, the McKinsey study stresses that its analysis is nothing more than ‘an initial attempt to determine the potential impact and cost-effectiveness of a subset of policy interventions’. [Dobbs, 2014, p36]

The likely impact of different interventions

Interventions analysed in the McKinsey study fall roughly into 16 ‘intervention’ categories. These are ranked according to their estimated impact on obesity and the strength of the evidence of their effectiveness (see Table 2, below).

This analysis shows that introducing a tax on products high in sugar (or fat) is one of the least effective interventions that can be made, ranking fourth last in the 16 categories analysed. Moreover, there is no direct evidence at all that such a tax brings about any change in weight, or even any change in consumption or physical activity levels. That a tax of this kind will bring about a positive changes in consumption, physical activity, or BMI is thus an unproven assumption, based on nothing more than a supposedly logical deduction from indirect evidence of other shifts. [Dobbs, 2014, pp38, 41]

Based on this analysis, the McKinsey study identifies the interventions that are likely to be the most effective. Its conclusions are as follows: ‘The highest impact intervention area is portion control, and this might also have the advantage of being profitable as there is a saving in ingredients. Reformulation of fast food and processed food is the second-highest impact intervention type, but here some costs are involved. Many of the other highest-impact interventions [are] parental education, introducing healthy meals in schools and workplaces, and changes in the school curriculum to include more physical exercise.’ Also worth considering, as the study shows, are workplace wellness programmes, which have an impact on weight levels and could probably be implemented at relatively low cost. [Dobbs, 2014, p42]

Adds the McKinsey study: ‘Our assessment finds that the single highest-impact intervention area is reducing the size of portions in packaged foods, fast-food restaurants, and canteens. This saves more than 2 million DALYs over the lifetime of the 2014 population.’ However, this translates into ‘about 4 per cent of the total disease burden attributable to high BMI’. It thus signals that even the intervention with the most impact will ‘achieve only a modest reduction in the overall burden of obesity’. Hence, if significant overall impact is to be achieved, this requires ‘as many interventions as possible…by as wide as possible a range of sectors of society – particularly if the aim is to shift cultural norms around eating and physical activity habits’. [Dobbs, 2014, pp42-43]

Table 2: Impact of obesity levers, United Kingdom, over lifetime of 2014 population

The strength of the evidence of any impact on obesity (see third column) ranges from:

■■■■■ Sufficient evidence of weight change

■■■■ Limited evidence of weight change

■■■ Sufficient evidence for behaviour change (reflected in changes either in consumption or in physical activity levels)

■■ Limited evidence for behaviour change (ditto)

■ Logic based on parallel evidence (no direct evidence for change in weight or change in consumption or physical activity levels, but logical deduction based on parallel or indirect evidence)

Category of intervention Estimated impact Strength of evidence

Thousand DALYs saved*

Portion control 2 126 ■■■

Reformulation 1 709 ■■

High calorie food/

beverage availability 1 137 ■■

Weight management

programmes 967 ■■■■■

Parental education 962 ■■■■

School curriculum 888 ■■■

Healthy meals 868

Surgery 615 ■■■■■

Labelling 575 ■■

Price promotions 561 ■

Pharmaceuticals 430 ■■■■■

Media restrictions 401 ■■

10% tax on high sugar/

high fat products 203 ■

Workplace wellness 139 ■■■■

Active transport 67 ■

Public health campaigns 49 ■

Source: Dobbs et al, Overcoming obesity, McKinsey Global Institute, p38; assessment based on literature review, expert interviews, MGI analysis

* DALYs or disability adjusted life years. DALYs capture the burden of poor health by measuring years of life lost and years of life impaired by a disease condition. [Dobbs, 2014, p40]

The media attention given to different types of intervention

The McKinsey study also examines media coverage of the various interventions that may be used to reduce obesity. It finds that the media tend to overlook the interventions likely to have the highest impact – and that media coverage focuses mainly on initiatives with little or no proven impact on either weight change or behaviour change, as set out in Table 3. [McKinsey, pp51-52]

Table 3: Estimated impact of interventions compared to their media coverage

Category of intervention Estimated impact Number of media counts

Thousand DALYs saved in past year in major UK news and business publications

Portion control 2 126 182

Reformulation 1 709 233

High calorie food/

beverage availability 1 137 n/a

Weight management programmes 967 13

Parental education 962 4

School curriculum 888 380

Healthy meals 868 n/a

Surgery 615 512

Labelling 575 350

Price promotions 561 114

Pharmaceuticals 430 364

Media restrictions 401 91

10% tax on high-sugar or

high-fat products 203 930

Workplace wellness 139 197

Active transport 67 n/a

Public health campaigns 49 n/a

Source: Dobbs et al, Overcoming obesity, McKinsey Global Institute, p52; assessment based on literature review, expert interviews, MGI analysis

This analysis shows that the interventions most likely to succeed are given very little coverage in the media. By contrast, by far the most media coverage is reserved for a 10% tax on high-sugar (or high-fat) products, even though there is no evidence at all that such taxes will result in changes in consumption and physical activity levels, let alone changes in weight or in obesity.

Though the McKinsey study does not spell this out, this skewed media coverage is also likely to skew policy interventions in favour of a sugar tax. In doing so, it is likely to downplay and distract attention away from alternative interventions with much greater prospects of success. This, of course, is likely to undermine the battle against obesity, rather than advance it in any meaningful way.

International experience regarding SSB taxes

The policy paper notes that ‘a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages has been implemented in various countries’, including (in alphabetical order) Denmark, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Mauritius, Mexico, and Norway.

According to the policy paper, SSB taxes in various countries have led to increased prices and reduced demand for taxed products: changes which it summarises as follows:

Table 4: Countries with SSB taxes and their impact on prices and demand

Country Date/rate of SSB tax Price increases Reduced demand

Finland 2011, €0.220/ per litre 7.3% in 2011 0.7% in 2011

on high-sugar drinks 7.3% in 2012 3.1% in 2012

2.7% in 2013 0.9% in 2013

France 2012, £0.059* per litre 5% in 2012 3.3% in 2012

3.1% in 2013 3.4% in 2013

Hungary 2011, $0.02 tax on certain 3.4% in 2011, 2.7% in 2011

high-sugar sodas 1.2% in 2012, 7.5% in 2012,

0.7% in 2013 6% in 2013

Mauritius 2013, 3c per gram of sugar no evidence cited no evidence cited

Mexico 2014, 1 peso per litre no evidence cited 10% in 2014**

Source: Policy paper, Appendix II and Appendix III

*The policy paper gives a figure in pounds sterling, rather than euros, but other sources put the tax at some 7.55cents per litre [Urbach, 2016, p6, citing Berardi, N. P Sevestre, M Tepaut, and A Vigneron, (2016) ‘The impact of a “soda tax” on prices: evidence from French micro data’, Applied Economics, pp1-19]

**This figure is at odds with the 6% reduction cited in a 2016 article on the impact of the tax, as well as data from Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health which shows increased SSB sales after the introduction of the tax (see Mexico’s SSB tax, below).

There are major discrepancies in the figures cited for price increases and (presumed) reductions in demand, raising doubts as to the strength of the causal link between the two. In addition, even if SSB taxes do succeed in reducing consumption of the taxed products, they will not necessarily reduce overall sugar intake because people may switch to cheaper brands, or shift to other sugared products (including coffee or tea), or cut down on other items so that they can still afford to buy the taxed items. [Urbach, 2016, pp3-4]

In addition, the policy paper makes little mention of the fact that Denmark abolished its SSB tax in January 2014, citing inflated prices, employment risks, and an impetus to cross-border shopping among its reasons, along with an increased administrative burden and evidence of hoarding and higher calorie intake. The decision reflected the Danish tax ministry’s view (expressed in 2012) that ‘suggestions to take foods for public health reasons are misguided at best and may be counter-productive at worst’. The ministry also warned that sugar taxes could ‘become expensive liabilities for the businesses forced to become tax collectors on the government’s behalf’. [Urbach, 2016, p6; KPMG, Taxing your sweet tooth: effective nudge or economic burden, May 2016, p4].

After the Danish tax was repealed, Alain Beaumont, secretary-general of the European soft drinks association Unesda, commented: ‘Soft drinks taxes are on the wane and are being voted down by governments and parliaments across Europe. They have not been proven to achieve any public health objectives and they destroy jobs and economic value.’ [Vegter, 2016, p6]

In addition, Ireland’s tax on soft drinks was introduced as far back as 1916, and was repealed in 1992, so it hardly provides a relevant example. The soda tax in Norway was introduced in 1981, which means it is unlikely to have affected the frequency of soft drink consumption in the period from 2001 to 2008, as cited by the policy paper. In addition, if there was indeed a decline in consumption in the 2000s (no supporting citation is provided), this was probably the result of the ‘complimentary (sic) measures’ taken, which included bans on advertising unhealthy food and drinks to children. [Policy paper, p13; Vegter, 2016, p6]

The policy paper makes no mention of other countries which have either abandoned SSB taxes or declined to introduce them. Iceland, for example, discontinued its sugar tax on beverages and foods in January 2015, saying this was necessary to benefit households and simplify the tax system. Romania considered introducing fast food and SSB taxes in 2010 and 2011 but abandoned the initiative in 2012, citing concerns about the difficulty of implementing the tax and industry warnings about potential job losses. [Urbach, 2016, pp5, 7]

Research by Ecorys, a leading European research and consultancy company, confirms the difficulty in determining the impact of SSB and similar food taxes in many of the European countries to which the policy paper refers. In July 2014 Ecorys published a report on Food taxes and their impact on competitiveness in the agri-food sector, which included an assessment of the impact of taxes on non-alcoholic SSBs. [Ecorys, Food taxes and their impact on competitiveness in the agri-food sector, Final paper, Rotterdam, 12 July 2014]

Having examined the impact of food and SSB taxes in Denmark, Finland, France, and Hungary, Ecorys concluded that ‘the effectiveness of such taxes in discouraging the consumption of the targeted foods or ingredients is…uncertain’. Many other factors are inevitably also at work, including changes in the costs of raw materials which may also influence price and demand. [Ecorys, 2014, Preface, p8]

Price increases, the study adds, are ‘generally associated with a reduction in the consumption of the taxed product’. However, these decreases are often proportionally smaller than the price increase, pointing to inelasticity in demand. In addition, ‘consumers may move to cheaper versions of the taxed product (brand substitution), or to non-taxed products or less heavily taxed products (product substitution)’. There is also, of course, no guarantee that substitute products will contain less sugar (or less fat or salt). There is thus no proven link between reduced consumption and positive changes on obesity or wider issues of public health. As the Ecorys study puts it: ‘To what extent changes in consumption resulting from a food or SSB tax actually lead to public health improvements is still widely debated, and evidence from academic literature is inconclusive and sometimes contradictory.’ [Ecorys, 2014, pp8-9]

However, the Ecorys study goes on, food and SSB taxes do indeed have an impact on firms active in the agri-food sector. Such taxes increase costs for the firm, including administrative costs. In addition, as the study cautions, ‘the profit margin for the taxed product is negatively affected which, together with the decline in demand for the taxed product, negatively impacts firm profitability.’ Worryingly, it adds, ‘the impact of these burdens on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is likely to be larger’. Food and SSB taxes may also lead to ‘a decline in the need for labour inputs and thus employment, especially at local level’. Moreover, ‘there are large numbers of local SMEs that manufacturers work with, mostly active in bottling, packaging, advertising, and retail’. Food and SSB taxes may thus ‘have a direct effect on local employment, as well as a trickle-down effect on employment through the value chain’. [Ecorys, 2014, p10]

Losses of this kind may sometimes be ‘compensated by growth in other product lines’, the study points out. However, this is not always the case – and ‘especially not for SMEs which do not have much flexibility to offset the loss of profit margins on other products’. In addition, even large multinational companies that produce only sweetened foods or beverages will find it difficult to switch to other products. [Ecorys, 2014, p11]

Like the McKinsey study, the Ecorys one notes that ‘food and SSB taxes are not the only options available to policy makers to impact on the consumption of foods and beverages with a high percentage of fat, salt, or sugar’. It thus outlines the various other steps that could be taken: from the subsidisation of fresh fruit and vegetables to the use of ‘information and education schemes’ to increase awareness of the importance of a balanced and healthy diet. [Ecorys, Executive Summary, pp11-13]

Mexico’s SBB tax

According to the policy paper, the SSB tax introduced in Mexico resulted in ‘purchases of taxed beverages decreasing by an average of 6 per cent…and decreased at an increasing rate of up to a 12 per cent decline by December 2014’. In addition, ‘reductions were higher among households of lower economic status, averaging a 9 per cent decline during 2014 and up to a 17 per cent decrease by December 2014, compared with pre-tax trends’. [Policy paper, p11]

These figures are taken from an article by Arantxa Colchero and others, entitled ‘Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages: observational study’. It was published in the British Medical Journal in January 2016 and seeks to analyse the purchase of beverages from January 2012 to December 2014 ‘from an unbalanced sample of 6 253 households’ in 53 cities in Mexico. [M Arantxa Colchero et al, Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages: observational study’, 6 January 2016, BMJ 2016; 352:h6704, www.bmj.com/content/352/bmj.h6704]

This study seeks to compare actual SSB consumption, by the end of 2014, a year after the implementation of a 10% tax on SSBs, with modelled consumption had the tax not been implemented, based on trends established in 2012 and 2013. It finds an average decrease in consumption of 6% over the year, as the policy paper stresses. However, the conclusions reached, as cited in the policy paper, may also be over-stated, especially as the authors acknowledge that ‘a major limitation of their work is that causality cannot be established, as other changes are occurring concurrent with the tax’. [Colchero, 2016, p6]

However, even if the full 6% average decrease could be attributed solely to the SSB tax – and not to an already apparent trend of declining soft drink consumption in the country – it would still be insignificant. According to the Colchero article, ‘during 2014 the average urban Mexican purchased 4.2 litres fewer taxed beverages’ over the course of the year. This translates into 11.5ml per person per day – which is roughly the equivalent of one less 330ml can of Coke per Mexican per month. [Colchero, 2016, Table 2 and p6] This is a meaningless reduction, which is unlikely to have had any impact on obesity.

In addition, sales data gathered by Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) seem to contradict the conclusions reached in the Colchero article, for the NIPH data shows that sales of SSBs in fact rose by 6.4% in 2014 and by 7% in 2015. [Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica,] ‘Why it is not possible to make determinations on the usefulness of the tax on sugar sweetened beverages in Mexico during 2015 using raw sales data’, undated, cited in Vegter, 2016, p4] The NIPH attributes these increased sales to confounding factors such as economic growth, higher seasonal temperatures, and the impact of marketing and promotions, which (it says) can increase consumption by up to 20%. The NIPH tries to argue for the effectiveness of the SSB tax in any event but, as Mr Vegter writes, ‘if industry marketing can totally overwhelm the effects of fiscal intervention in the consumption of SSBs, then the case for such an intervention is fatally undermined’. [Vegter, 2016, p4]

These conflicting assessments of SSB purchases in Mexico in the post-tax period underscore the difficulties in accurately measuring the impact of an SSB tax on the average consumption of taxed products. The extent to which an SSB tax might trigger brand or product substitution is even more complex and uncertain. What, if any, impact the tax might have on reducing obesity simply cannot be assessed on the limited data available. The Colchero article implicitly acknowledges this key weakness, saying its authors were unable to ‘quantify any potential changes in calories or other nutrients purchased and their potential health implications’. [Colchero et al, Beverage purchases, p11]

In 2015 the country’s lower house of Congress voted overwhelmingly (by 423 to 33) to approve a package of fiscal measures that includes a 50% cut in taxes on soft drinks with less than 5 grams of added sugar per 100ml. The aim is to encourage the industry to offer more diet colas and similar low-calorie options, which thus have never proved popular. There is as yet little impetus to abolish the tax altogether – despite its ineffectiveness in countering obesity – because it yields more than 20 billion pesos annually, according to the Mexican finance ministry. [Anna Yukhananov, ‘Mexican lower house votes to lower tax on sugary drinks’, Reuters, 19 October 2015; David Angren, ‘Benefits of Mexican sugar tax disputed as Congress approves cut’, The Guardian 22 October 2015]

The ‘mathematical model’ on which the policy paper relies

According to the policy paper, ‘a South African study estimated the effects of a 20 per cent tax on SSB on the prevalence of obesity and found a reduction in obesity of 3.8 per cent in adult males and 2.4 per cent in females’. [Policy paper, p17] The South African study in question is one by Mercy Manyema, a researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), and various other authors. Among these is Professor Karen Hofman, director of Priceless SA (Priority Cost Effective Lessons for Systems Strengthening), a policy unit based at the Wits School of Public Health.

Entitled ‘The Potential Impact of a 20% Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Obesity in South African Adults: A Mathematical Model’, the study was published in October 2014 (‘the Manyema article’). [Manyema M et al, ‘The Potential Impact of a 20% Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Obesity in South African Adults: A Mathematical Model’, PloS ONE 2014; 9(8):e105287] It draws significantly on an earlier study, which was written by Professor Hofman in conjunction with various other researchers, including Maria A Cabrera Escobar. This study is entitled ‘Evidence that a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages reduces the obesity rate: a meta analysis’ and was published in the Public Health journal of Bio-Med Central (BMC), a UK-based for profit scientific publisher (the Cabrera Escobar article). [Cabrera Escobar et al, ‘Evidence that a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages reduces the obesity rate: a meta analysis’, BMC Public Health, 2013 13:1072]

The 2013 Cabrera Escobar article

The 2013 Cabrera Escobar article sets out to ‘evaluate the literature on SSB tax and price increases, and their potential impact on consumption levels, obesity, overweight, and body mass index (BMI)’. Twelve articles published between January 2000 and January 2013 were identified as qualifying for evaluation, of which nine dealt with price issues (not always linked to SSB taxes), while three reported on the possible impact of SSB prices on BMI, overweight, or obesity.

Of the nine articles dealing with apparent price effects, six were from the USA and one each from Brazil, France, and Mexico. All these articles ‘showed negative own-price elasticity’, meaning that ‘higher prices were associated with lower demand for SSBs’. Four articles also reported ‘cross-price elasticities’ (ie, increased prices for alternatives), indicating that ‘higher prices for SSBs were associated with an increased demand’ for non-taxed products. [Cabrera Escobar et al, 2013, pp1,7]

According to the Cabrera Escobar article, a 10% price increase in SSBs is likely to lead to a 13% reduction in demand for them. The 13% figure is a ‘pooled elasticity estimate’ extracted from all these articles, each of which has its own varying estimate of ‘own-price elasticity: in other words, of how an increase in the price of a product is likely to reduce the demand for it. [Cabrera Escobar, 2013, p8] However, this estimate of how demand for SSBs may diminish in response to a price increase does not address the key additional questions of whether decreased demand for higher priced SSBs will in fact reduce overall calorie intake – or have any measurable impact on BMI and obesity.

Few of the articles evaluated dealt with the possible impact of an increase in SSB prices on BMI and obesity. Those that did, as the Cabrera Escobar article puts it, were difficult to compare because of ‘differences in interventions, outcomes, and populations, as well as a diverse range of food stores and vending machine outlets’. In addition, ‘the estimates’ which they put forward showed ‘significant discrepancies’ in results. For example, one 2010 study (by Fletcher J M) estimated that a price increase of 1% would have an impact on obesity prevalence of -0.0001 among adults, while a similar study by the same author, also in 2010, estimated that a price increase of 1% would have an impact on obesity prevalence of -0.009 among children and adolescents. [Cabrera Escobar, 2013, p11]

By contrast, another 2010 study (by Travis Smith and others) estimated that a price increase of 20% would have a -0.03 impact on obesity prevalence. A 2011 study by Euna Han and others estimated that a 10% increase in price would have an impact on obesity prevalence of -0.05 among women. By contrast, this same study estimated that a 10% price increase would have an impact on obesity prevalence among men of -0.34. By contrast, another study by Lisa M Powell and others, conducted in 2009, estimated that a 1% increase in the price of sodas sold at grocery shops was associated with a 0.012 increase in BMI. A similar study by the same authors estimated that a 1% increase in the price of soft drinks sold via vending machines was associated with a 0.0124 increase in BMI. [Cabrera Escobar, 2013, pp12-13]

Based on these limited and often conflicting estimates, the Cabrera Escobar article concludes that ‘the few available studies suggest that higher prices of SSBs may lead to modest reductions in weight in the population’. This, it suggests, ‘should be sufficient for policy makers to consider SSB taxation as part of a package of interventions designed to reduce the health and economic burden due to obesity’. However, the Cabrera Escobar article also stresses the need for further research, saying that this should probe not only possible ‘health gains’ but also the impact of an SSB tax on jobs, implementation costs, savings to the health sector, and revenue for the government. [Cabrera Escobar, 2013, pp12, 13-14]

The 2014 Manyema article

The 2013 Cabrera Escobar article is tentative on the link between increases in the price of SSBs and a possible resulting small reduction in the prevalence of obesity. The 2014 Manyema article is also tentative at times, for it concludes by emphasising the need for further research into various important issues, including: [Manyema, 2014, p13]

• ‘the possible effect of SSB consumption on the daily energy balance and weight change’;

• ‘the extent to which reduced SSB sales would have adverse economic or social consequences, such as job losses’, and

• ‘whether these adverse consequences would outweigh the benefits of reduced obesity’.

However, as Mr Vegter notes, the Manyema article also starts off with a clear objective, which is to ‘model the effect of a 20% SSB tax on the prevalence of obesity in South African adults’ and so ‘enable the Department of Health to consider this as a lever to prevent and reduce the burden of disease resulting from obesity-related NCDs [non-communicable diseases]’. [Manyema, 2014, p3; Vegter, 2016, p3]

The article begins by claiming that ‘it will provide evidence on the potential impact of fiscal policy on SSB consumption and obesity in South Africa’. [Manyema, 2014, p3] However, the article does not in fact provide any hard data or other evidence to support its claim that a 20% SSB tax will have a significant impact in reducing levels of obesity in South Africa. Rather, it sets out a ‘model’ of what might perhaps occur, which (as Mr Vegter writes) is ‘at best speculation based on a range of assumptions derived from the US, France, Mexico, and Brazil’. [Vegter, 2016, p3]

Among other things, the Manyema article uses data from SANHANES-1 to show that, on average, South African adults consume 184 ml of SSBs, 200 ml of unsweetened fruit juice, and 204 ml of milk a day. It assumes that SSBs have an average energy density of 1 800 kilojoules (kJ)/litre, while the equivalent figure for unsweetened fruit juice is 1 340 kJ/l and that for milk is 2 540 kJ/l. Based on the Cabrera Escobar report, it presumes that a 10% increase in the price of SSBs will lead to a 13% decrease in their consumption. It also cites research showing that a daily increase in energy intake of 94 kJ/day is likely to increase body weight by 1 kg for adults – and presumes that the converse will also apply (though this might not in fact be so). [Manyema, 2014, pp6-7, Table 1]

Based on such factors, the Manyema article estimates that a 20% SSB tax will result in a reduction in daily energy intake of anything between 9kJ and 68kJ, with an overall weighted average of some 36kJ. It further estimates that this reduction will result in a decline in obesity prevalence among South African men of between 0.4% and 7.2% (average 3.8%), and among women of between 0.3% and 4.4% (average 2.4%). As Mr Vegter notes, these are ‘very small changes, with a very wide range of uncertainty’. [Manyema, 2014, p8; Vegter, 2016, pp9, 3]

In addition, as the Manyema article acknowledges, if the average (3.8%) is in fact achieved among men, this will ‘equate to 0.5 percentage point change’. Moreover, if the average of 2.4% is indeed achieved among women, this will be ‘equivalent to a 0.8 percentage point change’. [Manyema, 2014, p8]

Notes Mr Vegter: ‘The Treasury policy paper cites only the 3.8% and 2.4% change figures, without explaining what they really mean. Using the Global Burden of Disease statistics for obesity, and assuming that the average changes predicted by the Manyema paper will be realised, these percentage changes mean male obesity will decrease from 13.5% to 13.0% of the population and, for females, the incidence will decrease from 42% to 41%. Such low numbers, speculative as they are, hardly seem to justify a substantial tax on a wide range of arbitrarily-selected products such as sugar-sweetened beverages.’ [Vegter, 2016, p3]

The Manyema article also makes some extraordinarily specific claims about how the numbers of obese South Africans will come down in response to a 20% tax on SSBs: by 142 217 for women and by 80 452 for men, yielding a total reduction in the number of obese people of 222 669. In fact, however, these figures are again averages of estimates varying widely on either side. Among women, the number that experience a reduction in obesity could be 16 550, though it might also rise to 265 039. Among men, the number experiencing such a reduction could be 16 060, though it might also go up to 147 284. [Manyema, 2014, p9]

In other words, even if all the assumptions on which these estimates hold true, the number of South Africans experiencing a reduction in obesity could be a mere 16 550 among women and a mere 16 060 among men. Moreover, even if 222 669 people were in fact to experience a diminution in obesity, this total would amount to only 0.4% of the South African population. Again, such low numbers, speculative as they are, hardly justify the introduction of a substantial tax on SSBs, which could have many negative economic outcomes.

In addition, the Manyema article is not based not factual evidence, but rather on five key assumptions of doubtful validity. First, it assumes that a 20% tax on SSBs will result in a 20% increase in the price of SSBs. Second, it assumes this price increase this will result in a major reduction in SSB consumption. Third, it assumes that this reduction in SSB consumption will lead to an average reduction in daily energy intake of 36kJ – though consumers could in fact shift to untaxed sugary products instead. This reduction is a negligible decline, representing only 0.34% of the required daily energy intake of an adult man, but the article nevertheless assumes that it will result in significant weight. Fifth, it assumes that this reduction in body weight will reduce the prevalence of obesity in South Africa by the stated (and wide-ranging) percentages, the basis for which is not adequately explained. [Manyema, 2014, Table 1; Figure 2; Vegter, 2016, p9]

The Manyema article claims to have taken proper account of substitution effects, but it has no factual data to support its estimates. Its conclusions are based solely on the limited and conflicting data about cross-price elasticities for fruit juice and milk provided by four of the nine studies evaluated in the Cabrera Escobar article (see above). (The remaining five studies did not include any data on cross-price elasticities.) [Cabrera Escobar, 2013, p9] However, these four (mainly US) studies are too limited a foundation on which to base the Manyema article’s claim to have ‘accounted for substitution of SSBs with other drinks through the use of cross-price elasticities’. [Manyema, 2014, p10]

The Manyema article also acknowledges some of the weaknesses in its methodology, including a ‘lack of SA-specific own- and cross-price elasticity data’. It recognises that ‘a lower own-price elasticity’, (as had been found in a report dealing with obesity in India, for example) ‘would lead to smaller changes in SSB consumption and subsequently more modest changes in obesity’. It also acknowledges that ‘its model does not include the substitution effect of other sweetened drinks such as coffee, tea, and hot chocolate’, whereas ‘other studies have shown that the demand for tea and coffee…goes up with SSB price increases’. It further admits that it made no attempt to ‘account for substitution of SSBs with other sugar-sweetened food items’, instead assuming that such substitution would not be significant. [Manyema, 2014, pp10-11]

As these acknowledged weaknesses underscore, the Manyema article cannot accurately predict likely substitution effects. Nor can it provide any evidence-based substantiation for the five key assumptions on which its conclusions about reduced obesity rest.

The policy paper overlooks all the many shortcomings in the Manyema article. Instead, it seizes on only two of the figures it provides: and simplistically cites these as evidence that a 20% tax on SSBs will indeed reduce the prevalence of obesity by 3.8 per cent among men and by 2.4 per cent among women. [Policy paper, p17]

Irrationality of the proposed SSB tax

As the weaknesses in the Manyema article underscore, there is little reliable evidence that a tax on SSBs will reduce the prevalence of obesity in any significant way. As the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in the UK – and many other commentators – have pointed out, models of the kind used in the Manyema article work only if all the assumptions on which they are based hold true. However, any causal connection between SSB taxes and diminished obesity breaks down if any of the underlying assumptions are in fact incorrect. [Christopher Snowdon, Director of Lifestyle Economics, IEA, ‘Sugar taxes: a briefing’, 11 January 2016]

As earlier indicated, there are several ways in which the chain from taxation to better health outcomes can break down. First, businesses with the financial capacity to do so may decide to absorb some or all of the cost of an SSB tax, rather than pass it on to consumers via higher prices. Second, if prices do rise, consumers may value the product enough to absorb its higher costs by making cuts elsewhere in their spending. This means that the demand for SSBs and other food products may be more inelastic than articles such as the Manyema one assume. Third, consumers may respond to the tax by switching to cheaper brands of the SSB, or by buying it in cheaper shops or informal outlets. Fourth, consumers may reduce their consumption of SSBs but buy more of other high-calorie products. [Snowdon, 2016, p2]

International experience also shows that the causal chain is in practice likely to break down in precisely these ways. When a soda tax was introduced in Berkeley (California), for instance, retail prices rose by less than half of the amount of the tax, probably because of price competition from neighbouring areas which did not have a similar tax. [IEA, Sugar taxes, p2]

Where prices do rise, a reduction in consumption may occur. However, this is generally likely to be less than anticipated, as the demand for food and SSBs is often inelastic, staying at much the same level despite higher prices. In Finland, for example, as the IEA study records, ‘a 14.8% increase in the price of confectionery coincided with a mere 2.6 per cent drop in consumption’. In addition, when the price of soft drinks rose by 7.3 per cent for two years running in Finland, consumption fell by less than one per cent in the first year and by 3.1 per cent in the second year’. [Snowdon, 2016, p3; Policy paper, Appendix III]

‘Sin’ taxes on cigarettes may be effective in reducing demand, but food falls within a very different category. Writes the IEA: ‘Unlike smoking, food is a biological necessity. If one source of calories becomes more expensive, consumers will switch to another food or drink product or to a cheaper variety of the same product. There is no guarantee that the substitute products will have fewer calories or be better for health. Since humans are hard-wired to seek out energy-dense foods, the most likely effect of taxing calorific products is, as Ryan Edwards notes in Preventive Medicine, that “consumers will probably increase their demand for cheaper calories, leaving obesity unchanged”.’ [Snowdon, 2016, p3, citing Edwards R (2012) ‘Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes raise demand for substitutes and could raise caloric intake’, Preventive Medicine 54(3-4): 284-285, at 284]

That sugar taxes have little impact on obesity has also been confirmed by research in both the US and Mexico. Writes the IEA: ‘Studying soda taxes in the US, Fitts and Vader (2013) conclude that their research “does not support the theory that soda taxes have a negative effect on body-mass index”’. An earlier research paper in the US also found ‘no statistically significant associations between state-level soda taxes and adolescent BMI’ (Powell et al, 2009), while another US study found that changes in food prices had no effect on obesity (Han and Powell 2011). [Snowdon, 2016, p4, citing Fits D and A Vader (2013), ‘The effect of state level soda tax on adult obesity’, Evans School Review 3(1):74-91; Powell L, J Chriqui, F Caloupka (2009), ‘Associations between state-level soda taxes and adolescent body mass index’, Journal of Adolescent Health 45(3):S57-63; and Han E and L Powell (2011), ‘Effect of food prices on the prevalence of obesity among young adults’, Public Health 125(3):129-35]

Some commentators have tried to discount these findings by arguing that the taxes in issue were not high enough to affect BMI. However, a 2014 US study has shown that, even in areas where soda taxes are unusually high, they still fail to have any effect on obesity. According to these authors: ‘Our results cast serious doubt on the assumptions that proponents of large soda taxes make on their likely impacts on population weight. Together with evidence of important substitution patterns in response to soda taxes that offset any caloric reductions in soda consumption, our results suggest that fundamental changes to policy proposals relying on soda taxes as a key component in reducing population weight are required’. [Snowdon, 2016, p4, citing Fletcher J, D Frisvold and N Tefft (2014) ‘Non-linear effects of soda taxes on consumption and weight outcomes’, Health Economics, 10 March 2014]

In Mexico, moreover, the extent to which SSB consumption came down in response to the country’s 10% SSB tax is disputed, as earlier noted. However, assuming the Colchero article is correct in reporting a 6% reduction in consumption of SSBs, it nevertheless puts the average decline in the consumption of sugary drinks at a mere 11.5ml a person per day (Colchero et al, 2016, p6). According to Tom Sanders, a professor nutrition and dietetics, this is ‘a drop in the caloric ocean’, whereas if obesity is effectively to be countered ‘long-term reductions in the range of 300-500 kcal/day are probably needed’. [Snowdon, 2016, p4, citing Science Media Centre (2016), ‘Expert reaction to study investigating Mexico’s sugary dinks tax and changes in sales of taxed beverages’, 6 January 2016]

In addition, as the IEA article points out, a systematic review of some 880 studies dealing with the assumed link between food and SSB taxes and the prevalence of obesity has found little evidence of this causal connection. Writes the IEA: ‘There is a striking contrast between theoretical studies, which generally predict that such taxes “work”, and studies of hard data in places that have actually implemented them, which generally show the opposite. Lacking real world evidence that sugar taxes are effective as health measures, campaigners continue to cite findings from crude economic models which do not adequately account for the ability of consumers to choose cheaper or discounted brands, to shop at cheaper shops, or to switch to alternative high-calorie food and drink products.’ [Snowdon, 2016, p5]

There is no rational basis, thus, for introducing an SSB tax as a mechanism to reduce obesity. It is also irrational to single out the sugar in certain beverages for the imposition of a tax, rather than the sugar found in other foods and drinks. As an editorial in Business Day has asked, why focus on the specified SSBs rather than on ‘sugar-rich tomato sauce or jelly beans?’ [Business Day 12 July 2016] The policy paper suggests that the sugar in SSBs is particularly damaging because these drinks have no compensating nutritional benefits, but there is little clear evidence to suggest that a calorie from one source is any more fattening than a calorie from another. [Roby Lyons and Christopher Snowdon, ‘Sweet Truth: Is there a market failure in sugar?’ IEA Discussion Paper, no 62, July 2015, p6]

In addition, there is little scientific evidence that sugar is ‘addictive’, as some proponents of an SSB tax have claimed. As the IEA writes, ‘although “eating addiction” may be a behavioural problem, it is not the result of inherently additive substances in food’. There is also little evidence of a clear causal link between sugar consumption and obesity. In the UK, Australia, and Canada, for instance, sugar consumption has gone down in recent decades, even as obesity has increased. [Lyons and Snowdon, 2015, pp7, 6; Patrick Luciani, ‘What Canada can learn from Mexico’s sugar tax: It’s no panacea for obesity’, www.theglobeandmail.com/...article28233833]

The same is true in South Africa, where sugar consumption decreased on average from 354 calories per day in 1990 to 300 calories per day in 2011, a 15% reduction. Despite this reduction, the obesity rate (according to figures compiled by the Food and Agriculture Organisation and the United Nations) went up over the same period, from 14% in 1990 to 19.6% in 2011. This 40% increase in obesity clearly cannot be linked to increased sugar consumption. Instead, it could well be the result of increases in the consumption of vegetable oils and poultry. [Oxford Economics, Economic impact of the proposed SSB tax, presentation to BevSA Board, August 2016] The increased consumption of these products has clearly added significantly to daily energy intake, even as average levels of physical activity have come down.

In addition, sugary drinks provide only a small portion of people’s energy intake: 3 per cent in Britain [Snowdon, 2016, p4] and the same in South Africa, according to Oxford Economics, a consultancy, in an analysis commissioned by the Beverage Association of South Africa (BevSA). [The New Age 8 August, The Citizen 9 August 2016] Hence, even if the consumption of SSBs goes down in response to a tax, this will have only a marginal impact on sugar consumption – and an even smaller effect on obesity. [Snowdon, 2016, p4; Oxford Economics, 2016]

Moreover, sugar consumption in South Africa is already relatively low. Writes Mr Vegter: [‘Tax on sugar-sweetened beverages is arbitrary and unnecessary’, August 2016, p9]

The SANHANES-1 survey assessed dietary sugar intake among South Africans on a scoring scale of 0 to 8. A score of 0-2 implies a person is accustomed to a low sugar intake, 3-5 indicates a moderate sugar intake, and 6-8 shows a high sugar intake. The mean score for South Africans was 3.0, which is at the low end of the moderate band. Among young people, the mean was slightly higher, at 3.47. A similar bias is seen towards urban formal areas, where the mean score was 3.36, and towards white consumers, who scored 3.44. Sugar intake is lowest among black Africans, and in rural and informal areas. These scores indicate that South Africans on average do not consume too much sugar.

In total, SANHANES-1 found that only 19.7% of South Africans have a high sugar consumption score, 38.2% consume moderate amounts, and the largest share of the population, 42.1%, has a low sugar intake. This distribution is similar to the distribution of fat intake among South Africans: only 18.3% have a high fat intake, 46.4% consume fat in moderate amounts, and 35.3% eat fat only in low amounts.

What this means, as Mr Vegter notes, is that ‘more than 80% of the population does not have a high sugar (or fat) intake. As a result, fiscal interventions will largely impact upon people that do not require it, especially among the urban and rural poor’. [Vegter, 2016, 9]

In addition, as the McKinsey study has stressed, the causes of obesity are multiple and complex, which means that the problem can only be addressed via a multi-faceted response. Moreover, there are many possible interventions which are likely to be far more effective than a tax on SSBs. South Africa’s proposed SSB tax is thus irrational. If introduced, it also runs the risk of creating the false impression that the obesity problem is being countered, when this is not so.

Obesity is also not the most pressing of the many health problems confronting South Africa. As Mr Vegter notes, the Department of Health (in its Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Obesity) puts the proportion of disability-adjusted (healthy) life-years (DALYs) lost to excess body weight and diabetes at 2.9% and 1.6% respectively. By contrast, ‘unsafe sex, interpersonal violence, alcohol harm, and tobacco smoking together account for more than half of all healthy life years lost’. [Vegter, 2016, p9] Overall, any reduction in obesity from the introduction of the proposed tax is likely to be marginal. By contrast, the tax could have various negative economic consequences, which must also be taken into account and weighed against the improbable health benefits of the intervention.

The tax envisaged and its likely economic costs

As earlier noted, the SSB tax will be an excise tax which will be levied at a rate of 2.29c per gram of sugar in those beverages which contain ‘added’ as well as ‘intrinsic’ sugars. Most SSB taxes in other countries are levied at a flat rate per litre (for example, R2 per litre), but the policy paper rejects this approach on the basis that it ‘taxes low sugar content SSBs at the same rate as high sugar content SSBs’ and provides no incentive for manufacturers or consumers to reformulate SSBs so that they have a lower sugar content. The Treasury acknowledges that a tax per gram of sugar is ‘administratively slightly more complex’, but claims that this is justified as it will help promote a shift to products with less sugar. [Policy paper, pp15-18]

However, what this approach also means is that no distinction will be drawn between the intrinsic sugars that many beverages contain and the ‘added’ sugars that are supposedly the target of the tax. By contrast, beverages with only intrinsic sugars, such as 100% fruit juices, will not be subject to the tax. Yet the sugar content of such beverages is generally the same, if not significantly greater, than the sugar content of products such as Coke. (A 330 ml can of Coke, for example, contains 35 grams of sugar, whereas the sugar content of the same quantity of orange juice, apple juice and grape juice is 31, 46, and 55 grams respectively.) [Vegter, 2016, p10] This adds to the irrationality of the tax.

A ‘duty at source’ (DAS) system will be used, which means that the tax will be collected from the producers or importers of SSBs, who are far fewer in number than the bottlers, transporters, wholesalers, and retailers that make up much of the remainder of the value chain. This DAS system is seen as easing the administrative burden on South Africa’s customs and excise service, which will be responsible for collecting the tax. [Policy paper, p20]

The SSB tax will be collected from producers and importers at the factory gates or at ports of entry. These producers and importers are expected – so as to maintain their current profit margins – to pass the full amount of the tax on to those further down the value chain, which will have to pay the higher prices for them and are expected, in turn, to pass these prices on to their own consumers. [Policy paper, p20]

The policy paper makes no attempt to quantify the likely tax yield or to assess what its overall economic costs might be. However, Oxford Economics, a consultancy, states that some 5.480 billion litres of soft drinks were sold in South Africa in 2015, of which roughly 80% or R4.377bn are likely to be subject to the proposed SSB tax. [Oxford Economics, presentation to SoftBev board, August 2016] Since a 330 ml can of Coke has 35 grams of sugar, the SSB tax on such a can would be 80c. Hence, the SSB tax on three such cans (roughly equivalent to a litre) would be R2.40. If the SSB tax on Coke is taken as the basis for calculating a rough total, the SSB tax on 4.377bn litres could yield R10.5bn in its first year – assuming there is no substantial decline in consumption. If this assumption holds true, the actual yield could well be higher, as there are more SSBs with a higher sugar content than Coke than there are SSBs with a lower sugar content, as data cited in the policy paper shows.) [Policy paper, Appendix IV, p29]

R10.5bn is a small part of overall annual tax revenues, currently amounting to around R1 trillion. [Business Day 12 July 2016] Such an additional tax would nevertheless be large enough to have a major negative impact on the soft drinks industry in South Africa.

How great the overall economic impact would be is, of course, difficult to predict, for all the reasons earlier outlined – including the extent to which the tax is passed through and the extent to which the consumption of SSBs in fact declines in response to increased prices. Demand for SSBs may well prove more inelastic than the 2014 Manyema article assumes. However, if this article is taken as definitive – as the policy paper believes it should be – then the economic consequences will be extensive.

Oxford Economics has modelled the likely impact of the proposed SSB tax, using both government-provided input-output tables as well as the elasticities (own-price and cross-price) set out in the Manyema article. Based on this data, it has estimated both volume changes in demand for SSBs and the probable economic consequences of the projected decreases. [Oxford Economics, BevSA presentation, August 2016]

At present, notes Oxford Economics, the beverage industry in South Africa contributes some R59.7bn in gross value added (GVA). (As the consultancy explains, GVA is a proxy linked to GDP via the following relationship: GVA + taxes on products – subsidies on products = GDP.) The industry also employs some 188 500 people, both directly and indirectly. Included within this total are some 14 500 individuals who are directly employed in the industry itself. Also included are roughly 107 500 indirect employees, whose jobs result from the procurement spending of the soft drinks industry in agriculture and elsewhere. Relevant too are some 66 500 people in the wider economy, whose jobs are supported by the spending of those in direct or indirect employment attached to the beverage industry. The beverage industry thus contributes significantly to GVA and jobs. It also pays some R17.9bn in taxes, a figure which includes R5.8bn in income tax, R4.5bn in corporate tax, and R7.6bn in VAT. [Oxford Economics, ibid]

On the basis of the elasticities cited in the Manyema article, Oxford Economics estimates that the consumption of taxed SSBs would decrease from 4.377bn litres to around 3.014bn litres. This would result in a R13bn reduction in the industry’s contribution to GVA. It would also bring about the loss of some 42 000 direct, indirect, and induced jobs. The industry’s contributions to income tax, corporate tax and VAT would decline from R17.9bn to R14.9bn, a decrease of R3bn. The industry would also have to pay some R7.6bn in SSB taxes (on the reduced number of litres consumed). However, the overall benefit to the fiscus from the new tax would be virtually cut in half by the R3bn reduction in its contribution to existing taxes. [Oxford Economics, 2016]

The SSB tax would also have a negative impact on the entire value chain, from agriculture (where some 79 000 people are directly employed in the sugar sector alone) [Sunday Times 17 July 2016] through to utilities, construction, the hospitality industry, the wholesale and retail sector, the transport industry, and the financial and business services sector, among others. In each of these spheres, current contributions to GVA would be diminished, jobs would be lost, and tax payments would come down – but without any offsetting contribution in these spheres from the new SSB tax. [Oxford Economics, 2016]

According to Oxford Economics, the retail sector would be particularly hard hit. It could well lose another 15 000 jobs (over and above those earlier identified), while between 10 000 and 20 000 anticipated jobs would become much more difficult to generate. Within the retail sector, the impact would fall most heavily on the informal and often home-based ‘spaza’ shops which currently employ some 360 000 people and which rely on soft drink sales for some 15% to 20% of their revenue. [Business Day 25 July 2016] The SSB tax would significantly reduce the sales and profit margins of these small enterprises, which could lead to the closure of between 6 500 and 11 500 of these outlets. Supermarkets and discount stores will find it easier to absorb the impact, but spaza shops – along with other local and traditional retailers – would be hard hit. [Oxford Economics, 2016]

The South African economy already stands on the brink of recession and the downgrading of its international credit ratings to sub-investment (junk) status. The country also confronts a major crisis of joblessness, with the unemployment rate already standing (on the broad definition which includes discouraged would-be workers) at 36% in general and at 67% among young people aged 15 to 24. No other country that has seen fit to introduce a sugar tax has confronted an equivalent burden of joblessness. In circumstances such as these, South Africa simply cannot afford to put between 55 000 and 60 000 jobs at risk – and especially not when the claimed health benefits of the proposed tax are most unlikely to be realised.

If the SSB tax is introduced, demand for taxed products is likely to prove more inelastic than the Manyema article assumes. In this event, the consumption of taxed SSBs will not decrease as sharply and the negative impact on GVA, jobs, and tax revenues within the soft drinks industry will be much reduced. However, the health rationale for the SSB tax will also then be shown to be deeply flawed, raising yet further questions as to why the tax should be imposed at all.

In addition, the SSB tax will be a regressive measure with a particularly negative impact on low-income households, which spend a significantly higher proportion of their overall income on food and beverages than wealthier households do. Writes Mr Vegter: ‘It is well established that poor people seek out foods high in energy, since this offers the most economical choice. As a share of their income, the poor spend 1.3% on mineral water, soft drinks, and fruit and vegetable juices. The rich spend only 0.55% of their income similarly. As a consequence, a tax on SSBs will undoubtedly be regressive, hitting the poor harder than the rich.’ [Vegter, 2016, p10]

The policy paper discounts this adverse consequence on the basis that the poor – who generally suffer higher levels of obesity than the rich – will benefit the most from the diminution in obesity that the SSB tax will supposedly bring about. But if that diminution proves marginal at best, as is likely to be the case, then there will be little compensating benefit for the poor. In addition, since 80% of the population does not have a high sugar (or fat) intake, as SANHANES-1 shows, most South Africans will have no need of the supposed health advantages of the tax and will derive no benefit from it at all. [Vegter, 2016, pp10, 9]

Also relevant is the fact (as Mr Urbach has pointed out) that the limited budgets of lower-income households leave them with a narrower range of purchasing choices, while lower-income areas generally have fewer retail and food outlet options. The combined effect may be to make it difficult for low-income households to change their consumption patterns in response to this regressive tax, even if they would like to. [Urbach, 2016, p6]

Perversely, the tax will also signal to consumers that they ought to switch from taxed products, such as Coke, to 100% fruit juice, which is to be exempt because it has only ‘intrinsic’ rather than ‘added’ sugars. But a 330ml can of certain fruit juices contains even more sugar than a 330ml can of Coke: 46 grams for apple juice and 55 grams for grape juice, as compared to 35 grams for Coke. At the same time, these highly sugared 100% fruit juices are roughly 60% more expensive than most SSBs. Hence, as Mr Vegter writes, those who make the switch will incur significant costs – and without any compensating gains in health benefits at all. [Vegter, 2016, p10]

Also important is the fact that South African consumers already confront a host of daunting challenges. For many months the inflation rate has exceeded the South African Reserve Bank’s target band of 3% to 6% a year, while it stood at some 6.3% in June. Inflation has been driven by food, petrol, and electricity price increases, along with rising interest rates, and cannot easily be contained. In addition, the proportion of consumers already seeking credit to cover their daily living costs is higher in South Africa than in most other countries, standing at 86% compared to a global average of 40%. As a result, the number of individuals having to seek debt relief is already growing exponentially. [KPMG, 2016, p6] In circumstances such as these, the price increases the tax is intended to bring about could cause significant harm to consumers who are already over-stretched.

The tax is also likely to have a particularly adverse impact on small retailers – a consequence that has already been demonstrated in France. Price competition there between the large retailing groups made them reluctant to pass on the tax in full to their customers. However, the largest retailers also had the negotiating clout to bargain with producers for an ‘under-shifting’ of the tax to them, which meant that the producers passed on less than 100% of the tax to these particular firms. By contrast, smaller retailers had less bargaining power, which meant that producers passed the tax on in full to them. This then left with two damaging choices: they could either pass the tax on in full to their customers and risk a reduction in sales, or they could absorb a part of it, which would reduce their profit margins. Most were unable to reduce their profit margins, so they passed the tax on in full. The upshot, as a 2016 study shows, is there was a higher pass-through on to lower-priced products aimed at low-income households. [Urbach, 2016, p6, citing Berardi (2016)]

Not the most ‘cost-effective’ policy option

The policy paper describes the proposed SSB tax as the most ‘cost-effective’ option available to help counter obesity. What the Treasury really means, however, is that the tax is the cheapest way the government can (purport to) tackle the obesity problem.

As the policy paper notes, implementing a fiscal measure like the SSB tax is likely to cost only R0.20 per head to implement (according to 2010 data). By contrast, regulating food advertising would cost R0.90 per head, while food labelling would cost R2.50 per head, worksite interventions would cost R4.50 per head, mass media campaigns would cost R7.50 per head, school-based interventions would cost R11.10 per head, and physician counselling would cost R11.80 per head. [Policy paper, p6, citing Table 2, National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Obesity 2015-2020] In other words, implementing an SSB tax will (not surprisingly) be cheaper for the government to implement than any other measure, but whether it will be effective in countering obesity is doubtful.

Across the world, food and beverage taxes, as the McKinsey study has shown, are among the least effective ways of overcoming obesity. Moreover, because obesity has so many and such complex causes, it can be countered only through a wide range of interventions. The policy paper implicitly acknowledges this when it claims that the SSB tax will be part of a ‘comprehensive package of measures’ aimed at stimulating ‘healthy food choices’, promoting physical activity, educating and mobilising communities, and establishing ‘a surveillance system’ to strengthen monitoring and evaluation. [Policy paper, pp6-7]