South Africa is grappling with its position in the global economy amidst the resurgence of emerging markets, known as the “rise of the rest.” While many developing nations are gaining momentum, South Africa’s economic performance has lagged behind, with declining rankings in key areas like technology and trade. To seize opportunities from this global shift, South Africa must address its low investment levels and reinvigorate its growth trajectory.

Terence Corrigan

In a recent column in the Financial Times, Ruchir Sharma discussed what has been referred to as “the rise of the rest”: the rapid development of a heterogenous group of non-Western economies, which cumulatively stand to reorientate global industrial and financial power. A phenomenon noted in the early 2000s, it slumped in 2010, and now appears back on track.

As the piece notes: “A major comeback is under way. After weakening sharply in the past decade, emerging economies are rebuilding their growth lead over developed economies, including even the strongest one, the US, to levels not seen in 15 years. The proportion of emerging economies in which per capita GDP is likely to grow faster than the US is on course to surge from 48% over the past five years to 88% in the next five. That share would match the peak of the emerging world boom in the 2000s.”

Noteworthy, too, is that what is taking place today is not dependent on the barreling forward of the Chinese behemoth. No: countries across the developing world are making their mark. China is in fact slowing down.

Revealing though coincidental is that these thoughts appeared as South Africa was preparing for a state visit to China, and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. A clutch of agreements has been concluded, with an interesting stress on agricultural cooperation (shipments of South African avocados are set to begin, having been agreed to last year).

In addition, South Africa is gearing up to assume the presidency of the G20, the global colloquium of the largest economies.

Both engagements signify impulses in South Africa’s global positioning: its striving for diversified relationships across the world, particularly with countries of “the rest”, and its commitment to multilateralism. South Africa’s conception of itself is of a country of the “Global South”, carrying the torch for a revitalised Africa, in the thick of the work to create a new, multilateral world order.

A country’s role in the world is determined on multiple fronts, but the “rise of the rest” is fundamentally one of economic standing – not only of raw size, but whether economies are robust and competitive, and can hold their own in the world. Equally importantly, can they fulfil the expectations and aspirations of the populations of the host societies?

Numbers tell important stories, and comparative numbers are especially illustrative. It would not be controversial to say that South Africa’s economic performance has fallen short for a long time; what may be under-appreciated is the extent to which it has fallen short in relation to its peers.

South Africa’s is a sizeable but modestly proportioned economy. World Bank data – useful for comparisons across the world – put its GDP at US$377.8 billion in 2023. In these terms, it is 40th in the world, not dissimilar in size from jurisdictions like Hong Kong, Colombia and Nigeria. (The figure for the world economy, by the way, stood at US$105 trillion.)

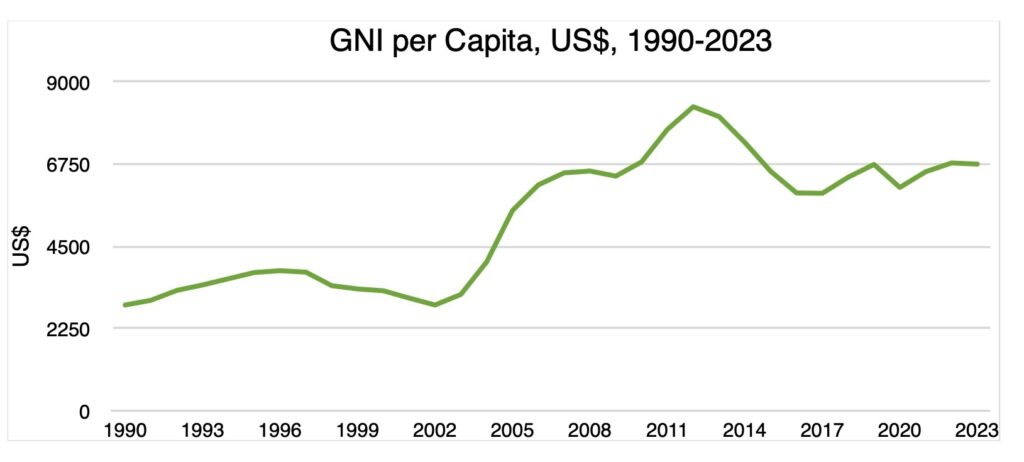

South Africa is classified by the World Bank as an upper-middle-income country; that is, its per capita Gross National Income (differing from GDP in accounting for income earned abroad) falls between $4 516 and $14 005. South Africa recorded US$6 750, ranking 105th in the world, coming in between Colombia and Azerbaijan. This is also significantly below the average GNI per capita for upper-middle-income countries, US$10 588, and also only slightly above the average for the middle-income group as a whole (those with per capita GNI of between US$1 146 and $14 005), which stands at US$6 379.

Interestingly, per capita GNI, on a long-running upward trend, has fallen markedly overall since 2012.

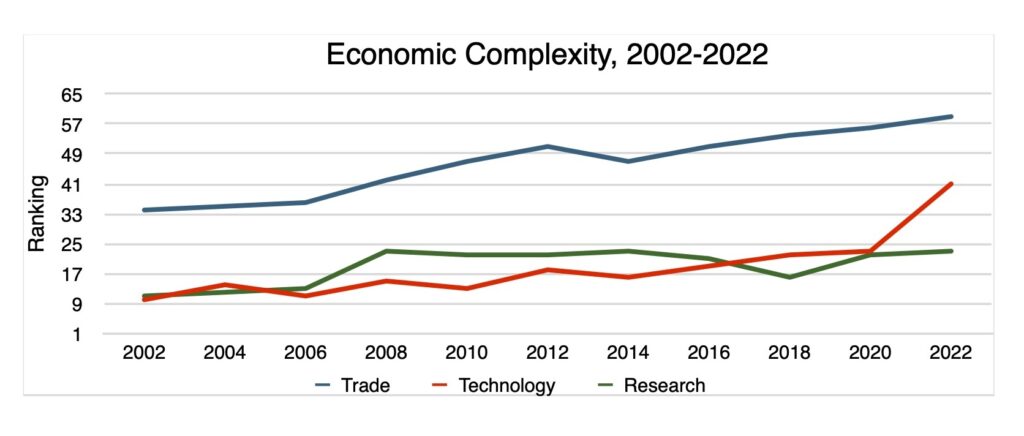

If anything, South Africa has been losing ground globally. One measure of this is the complexity of its economy: how adept and competitive a given jurisdiction is in multiple areas of activity. Complex economies are able to leverage diverse opportunities and, crucially, to engage in innovative and higher value-adding activity. The latter is critical for competitiveness in today’s global economy.

The invaluable Observatory of Economic Complexity presents data over decades on economic complexity across a number of fields. In 2002, South Africa was ranked 34th globally for trade, 10th in technology, and 11th in research. By 2022, these had declined to 59th, 41st and 23rd respectively. While these are ranks (and therefore relational), in each case the underlying scores used to determine South Africa’s standing had also fallen.

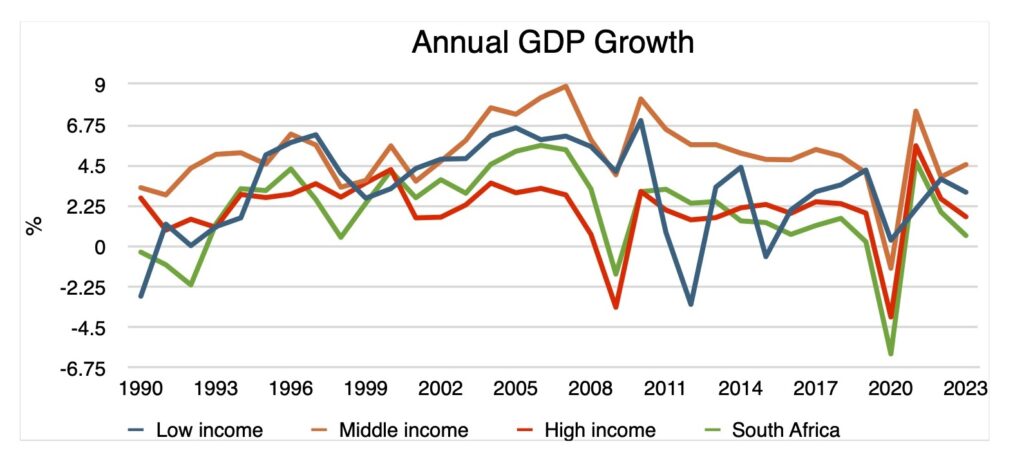

The sum of all this is reflected in the direction that the economy has travelled over recent decades, in other words, its economic growth rates. A growing economy signifies more wealth, more opportunities and – in a globalised age – more interaction with the outside world. As a rule, growth is simpler at the lower reaches of development. Poorer, less sophisticated economies grow by doing “more” of what they were doing before. More advanced economies tend to make their progress by doing things “better”. Growth becomes most restrained in the most advanced economies, for numerous reasons: the size of economies means new activity tends to be reflected in relatively small percentage contributions and increases (and hence small percentage point growth increases), while economic progress demands undertaking “new” and innovative activities.

The biggest winners over the past three decades have been middle-income countries. With a combination of favourably priced and adequately skilled labour, and satisfactory infrastructure, they have benefited mightily from the offshoring of manufacturing and increasingly of service industries from the wealthier parts of the world. It’s a simple cost-benefit analysis. This is illustrated below.

Concerningly, South Africa’s trajectory has been distinctly sub-par, tracking at around half – if not less – that of other middle-income countries. In that last decade, it has fallen below that of high-income countries.

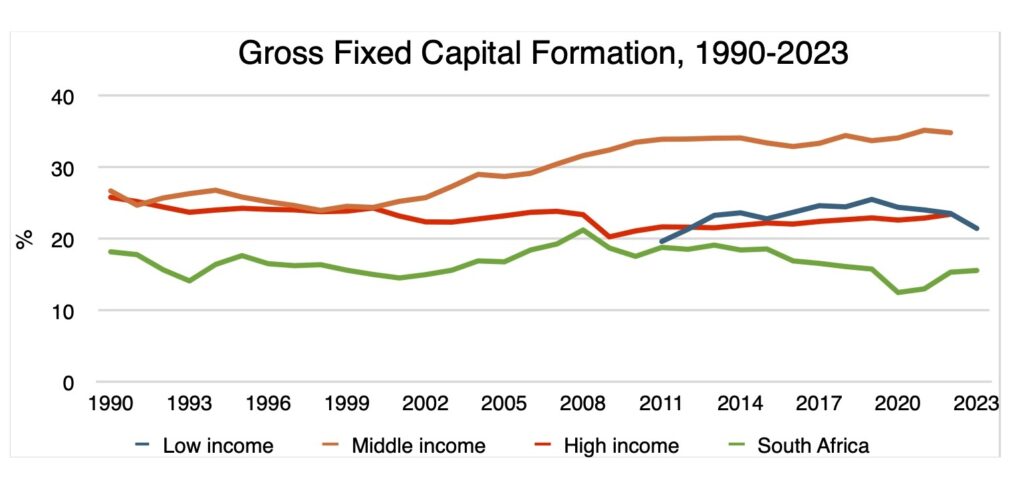

Behind this lies the level of investment. This is the funds sunk into factories, supermarkets, roads, railways and so on – assets that create wealth, or make wealth creation possible. Here again, global trends put this into perspective. Middle- and high-income countries entered the 1990s with nearly identical rates of investment, a little above 25% of GDP. By the start of the millennium a clear divergence was taking place, and the middle-income group went on strongly to outperform their high-income peers. Middle-income economies have managed investment rates in excess of 30% for well over a decade. Data for the low-income group is patchy, but it lagged behind the middle-income group. (This probably reflects the better economic growth and widening circles of opportunities in middle-income economies, as well as an increasing capacity for endogenous investment in them.)

South Africa, however, invariably fell short in each of these groups. It entered the 1990s with an indifferent level of 18% – unsurprising, given the prevailing instability and uncertainty – but has never been able to gain the traction that would increase growth sustainably. The National Development Plan envisaged getting an investment rate of 30% of GDP per annum, to drive a growth rate of some 5.4%. Yet, it has only managed a level of investment of over 20% in one year since the 1990s. In 2023, investment was less than 16% of GDP.

South Africa remains stuck on a low-growth path, fundamentally a matter of an inability to attract the investment that would drive it. And as long as this persists, the country will forgo whatever opportunities might exist to profit from the “rise of the rest”. Indeed, it might well see not only its chance at rapid gains eroded, but so too its status as a middle-income country, as its peers become ever more prosperous and today’s less affluent societies position themselves to step into opportunities that these economic shifts create. It stands to be part of a discarded “rest of the rest”.

South Africa is, however, not without advantages and prospects. Provided it changes course, the coming decades could be ones of prosperity with the attendant rise in living standards and global standing. The following column will discuss how this is possible.

Terence Corrigan is the Project Manager at the Institute, where he specialises in work on property rights, as well as land and mining policy

https://www.biznews.com/thought-leaders/2024/09/10/terence-corrigan-sa-best-rest-part-1

This article was first published on the Daily Friend.

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

LETTER | Rethinking BEE premiums could unlock billions for growth - Business Day

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

IRR’s 2026 Budget tips for Minister Godongwana

Feb 19, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Corruption-busting must begin with next week’s Budget – IRR

Feb 18, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Hold Ramaphosa to account for his SONA admissions of failure, IRR urges MPs

Feb 17, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026

Corrigan pt. II: FMD crisis — How did we get to this point? - Biznews

Feb 16, 2026