Terence Corrigan

South Africa’s farming economy exists at some remove from the day-to-day life of a rapidly urbanising population, visible largely through typically reliably stocked grocery aisles.

For the country’s political class, it is frequently little more than a signifier onto which to project ideological prejudices, but whose realities are poorly understood. For both, the Foot and Mouth epidemic needs to force a reassessment.

Foot and Mouth Disease is a viral disease that attacks cloven-hoofed animals – such as buffalo, cattle, sheep, and goats, along with pigs – both wild and domestic; it manifests in blisters, salivation, fever and lameness. While not inherently fatal to mature animals (mortality ranges between 1% and 5%, although it can be as high as 20% among the young), subsidiary issues, such as an inability to eat, the infection of lesions and mastitis can prove fatal. Infection also risks weakening an animal in the long term.

“The disease is relentless. It spreads rapidly and is highly contagious.” This is an apt description from Stats SA in a comment from 2022. It can be spread by contact between animals, or by any number of other vectors: contaminated pens, feed or animal products, as well as by humans, in clothing, footwear and on vehicles and equipment.

The Background

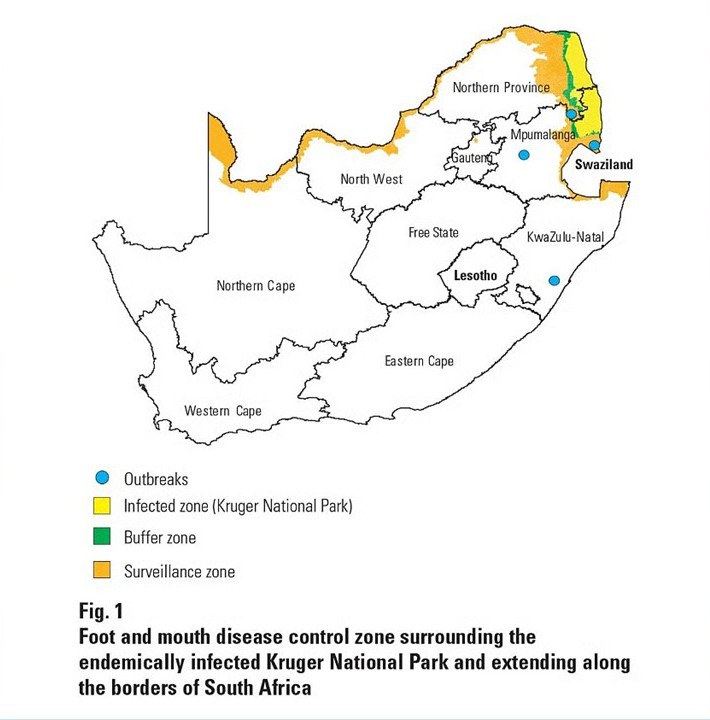

First apparently noted in early sixteenth century Italy, FMD has spread across the world, with each continent having at some point experienced it. South Africa saw its first officially recognised outbreak in 1892, but anecdotal evidence suggests that it was known beforehand. It remained endemic in parts of what is now Limpopo and Mpumalanga, largely borne by buffalo in the Kruger National Park, although a system of fencing and monitoring in this region kept it at bay. In 1995, South Africa – having had no outbreaks since 1957 – applied to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, Office International des Epizooties) for recognition as an area free of FMD without the need for vaccination. The Kruger National Park was acknowledged as an FMD zone, while the areas adjoining it were declared a buffer zone in which cattle were required to be vaccinated; various other parts of the country, along the buffer zone and along most of its land border were deemed surveillance zones. This status was lost as a result of outbreaks in 2000 and 2001, though reinstated in 2002 after they had been brought back under control.

Source: Brückner et al, “Foot and mouth disease: the experience of South Africa”, Revue Scientifique et Technique de l’OIE, 21(3), 2002, p. 752.

However, in 2019, South Africa was again hit with an FMD outbreak. This represented a turning point of sorts, for South Africa has never been able to recover its FMD-free status. Since then, as Minister of Agriculture John Steenhuisen has said, “our farmers have faced unprecedented challenges.”

Or, as Johan*, one of the farmers approached for this piece, put it: “Terence, it’s bad.”

The outbreak that won’t stop

This is quite correct. The current outbreak may only recently have shifted attention from agribusiness journals and provincial news pages to daily headlines, but it has been close to five years in the making. It dates from May 2021, where the disease emerged in a communal grazing area in the Mtubatuba area of KwaZulu-Natal. FMD has been a constant presence and ongoing concern for the farming economy, commercial and subsistence ever since, seemingly gathering momentum as time went on. 2025 saw some 24 200 cases, close to three times the 7 700 recorded in 2022; FMD is now present in eight of the country’s nine provinces.

Comments Johan: “It’s been like a fire that starts at one point and spreads. The wind comes up and you can’t stop it.”

The impact of the disease has been profound. The Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy, an agribusiness consultancy, estimates that beef industry alone will take between R3.2 billion and R11.3 billion in losses, while foregone export earnings could push this figures up to R13.1 billion. (Biosecurity is a particularly sensitive matter for foreign markets, and the FMD outbreak has already closed some foreign markets, such as China and some of South Africa’s neighbours.) The dairy industry could take a blow in the magnitude of R1 billion.

This has been paired with rising pressure on consumers. Meat prices rose by 12.2% between December 2024 and December 2025, well in excess of the annual consumer price inflation rate of 3.6% – the highest of any item in the basket making up the consumer price index. Beef prices have, unsurprisingly, been especially hard hit. For South Africa’s struggling with costs of living – a key objective for the Government National Unity – this is an increasingly personal experience.

But it is on the country’s farms that the crisis is seen in its most acute form. To give an overall picture of this, Emma Kean, consultant to Intelact – an advisory firm to the dairy industry – shared some modelling with The Daily Friend. This was based on a survey of farms across KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, conducted in conjunction with her colleagues and an associated farmer, Tom Turner: 25 of these had recorded FMD outbreaks (in other words, where there were positive cases), 37 had been able to vaccinate against the disease, and 151 were vulnerable to it. (As the survey was conducted in early January, it is likely that many more are now “positive”.) Each of these held an average of around 800 cows. The results suggested that the cost per cow for each “positive farm” was R6 000; for each vaccinated farm, R1 784; and for each vulnerable farm, R1 704. These costs encompassed production losses, culling, the costs of healthcare, early culling and additional labour and biosecurity.

These amount to multi-million-rand costs for each individual farm. Says Kean: “Considering that these are not massive corporations, but family owned and operated enterprises, many will not survive this, with great cost to their employees, communities and the dairy industry.”

This meant that the positive farms would take cumulatively losses of R120 000 000; vaccinated farms, of R54 582 400; and vulnerable farms; of R205 843 200. This amounts to some R380 425 600 – or well over a third of a billion rand, on those farms alone. The total cost across the whole country stands be several times higher.

In purely business terms, farms are not cash-rich enterprises. Their value is in their assets, which are continuously leveraged to provide operating capital. Maintaining a reasonable asset to debt ratio (around 1.6:1) is prudent. The disruption of activity pushes ratio ever more strongly towards debt, which risks creating a ballooning problem in the future. This is a reality that farmers hit by FMD face.

Andre*, a beef farmer and breeder, provided a stark account of how FMD had hit his operations: “It hit as our breeding season began. The first visible losses were calves who died of heart diseases, 30 or so. The biggest loss, however, has been the breeding season itself. We’ve been at a complete standstill. The timing was perfectly bad. Our bulls are completely out of action, they are so badly incapacitated. This means a massive, massive financial loss. We usually sell pregnant females, but there are none now. Weaner weights are dramatically down. It all goes on adding up. This will have delayed consequences in the years ahead. I breed most of my replacement bulls, and in a few years, I will have none of them.”

Derek*, meanwhile, runs a dairy. “Think of this as Covid for cows,” he says sardonically, pointing to the quarantine imposed when FMD appeared on his holding. He points out that even when milk is collected, it needs to be double pasteurised, which is a costly process, raising the cost of the milk accordingly. “If it gets into cows, the lactation may not recover. The knock-on effect could be devastating for the next three years, especially if regular and appropriate vaccines are not administered.” If the disease cannot be brought under control, the damage could last a lot longer.

Nor is this confined to commercial farmers. Livestock – particularly cattle – are a common unit of value in South Africa’s rural parts (“they are the ATMs of rural communities”, as one observer told The Daily Friend). The disruption of the trade in cattle, or worse, the incapacitation of cows and the loss of calves, has severely undermined rural households’ economic wellbeing. That this had hit during December only aggravated things: this is the time at which cattle are sold to fund end of year celebrations and to pay for education costs. Restrictions, even if unevenly enforced has severe repercussions for households dependent on trade in their livestock.

Beyond the socio-economic impact of FMD, it has had a profound psychological effect. “There’s a lot of mental stress,” says Derek, “farmers are dealing with a crisis that threatens them, their families and their workers. They are also seeing their animals suffer. It’s a horrible situation.”

Indeed, it is. Theo de Jager, chair of the Southern African Agricultural Initiative has described the outbreak as the worst livestock disaster South Africa has ever experienced (the 1896-97 rinderpest epidemic probably has a stronger claim on that title, but that is cold comfort for those facing FMD). This raises the question as to how we arrived at this point, what can be done to address this crisis. These questions will be explored next week.

* Names have been changed at the request of the individuals concerned.

Terence Corrigan is the Project Manager at the Institute, where he specialises in work on property rights, as well as land and mining policy. A native of KwaZulu-Natal, he is a graduate of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg). He has held various positions at the IRR, South African Institute of International Affairs, SBP (formerly the Small Business Project) and the Gauteng Legislature – as well as having taught English in Taiwan. He is a regular commentator in the South African media and his interests include African governance, land and agrarian issues, political culture and political thought, corporate governance, enterprise and business policy

https://www.biznews.com/intelligence/fmd-crisis-terence-corrigan

This article was first published on the Daily Friend.

Cut BEE premiums to put residents ahead of tenderpreneurs, IRR tells provinces

Mar 12, 2026

Cut BEE premiums to put residents ahead of tenderpreneurs, IRR tells provinces

Mar 12, 2026

SA’s economic mood is brighter, but fundamentals lag

Mar 11, 2026

SA’s economic mood is brighter, but fundamentals lag

Mar 11, 2026

Why South Africa still needs naval diplomacy - DefenceWeb

Mar 10, 2026

Why South Africa still needs naval diplomacy - DefenceWeb

Mar 10, 2026

Provinces must do more than just pay lip service to value for money – IRR

Mar 10, 2026

Provinces must do more than just pay lip service to value for money – IRR

Mar 10, 2026

LETTER | Country deserves value for money - Business Day

Mar 10, 2026

LETTER | Country deserves value for money - Business Day

Mar 10, 2026

Cut BEE premiums to put residents ahead of tenderpreneurs, IRR tells provinces

Mar 12, 2026

Cut BEE premiums to put residents ahead of tenderpreneurs, IRR tells provinces

Mar 12, 2026

SA’s economic mood is brighter, but fundamentals lag

Mar 11, 2026

SA’s economic mood is brighter, but fundamentals lag

Mar 11, 2026

Why South Africa still needs naval diplomacy - DefenceWeb

Mar 10, 2026

Why South Africa still needs naval diplomacy - DefenceWeb

Mar 10, 2026

Provinces must do more than just pay lip service to value for money – IRR

Mar 10, 2026

Provinces must do more than just pay lip service to value for money – IRR

Mar 10, 2026

LETTER | Country deserves value for money - Business Day

Mar 10, 2026

LETTER | Country deserves value for money - Business Day

Mar 10, 2026